What is organic certification, and how does LiteFarm support it?

- Larisse Cavalcante

- May 14, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2024

In a previous press release, we explored the definition, history, and associated benefits of organic agriculture. Today we will delve into the certification process that underpins organic labelling. To be deemed organic, a product must successfully navigate a rigorous certification process created to inform consumers, assure quality, and prevent fraud. There are two primary processes of organic certification: Third-Party Certification and Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS). In this post, we will briefly define and examine both, highlighting how LiteFarm facilitates and simplifies the organic certification process for farmers in 155 countries.

Organic certification involves the verification of agricultural products, spanning food and other goods, against specific standards established by organic farming organisations and/or government agencies. The list is extensive and while variations may exist from country to country and according to local legislation, the fundamental principles include:

The general exclusion of most synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, veterinary drugs and genetically modified organisms (GMO)

A defined set of animal welfare practices, including access to outdoor areas and the use of organic feed

Establishment of buffers between organic and surrounding conventional farms

Maintenance or the enhancement of biodiversity and soil and water quality

A mandatory transition period which can range from 2-3 years for fields that have been conventionally farmed

Now that we have a better idea of what is typically required for a farm to be organic, let’s focus on the two main certification processes.

Third-party Certification

In a third-party certification process, auditors verify that farms meet these organic production standards. Pollyanna Quemel, a Lead Auditor with QIMA IBD specialised in Brazilian, European, and United States Organic Legislations, described to us the critical steps for farmers seeking certification. These steps include identifying the products the farmer wishes to certify and selecting the appropriate organic standards that align with their intended market, such as Brazilian, European (CE), or United States (USDA) regulations. Following this, the certification body analyses the farmer's documentation, such as the Management Plan — a document that specifies practices and strategies to adhere to organic farming. The organic management plan is then rigorously reviewed during an audit at the crop and/or animal production or processing unit, which includes observing the production areas and facilities, interviews with staff and other procedures.

Pollyanna says (translated from Portuguese):

“Organic Agriculture encompasses a wide and varied range of farming practices, each adaptable to the specific realities of the local environment, yet all aligned with the principles of sustainability and ecological responsibility. As environmental consciousness and social responsibility have become more established, there has been a growing desire for agricultural and food practices that are more harmonious and balanced. Within this context, the journey towards organic certification has evolved.”

She goes on to highlight the benefits for farmers to get certified:

“Consumers are increasingly concerned about avoiding pesticides and opting for a balanced and nutritious diet. The market (for organics) is growing and consumers are looking for healthy and sustainable alternatives.”

Pollyanna inspecting an açaí (Euterpe oleracea) plantation at an organic farm in Brazil.

Despite the growing market demand for organic products, the decision to transition away from conventional farming can stem from a variety of motivations. In 2016, Vasant Jante embarked on conventional farming with just one cow on a 5-hectare plot of land in India. However, concerned about how his team was treating the land and the animals, he soon realised that something was amiss. He explains:

"The widespread use of pesticides like glyphosate to control weeds led to scorched fields, while chemicals were liberally sprayed to combat pests, and excessive fertilisers were applied in pursuit of higher yields. Recognizing this issue, I made a pivotal decision to transition to organic practices."

Vasant Jante (on the right) and his colleague on a farm in India.

Determined to embark on a journey of self-education, Vasant began watching online videos and seeking guidance from fellow organic farmers. He recalls:

"Between 2017 and 2019, I visited over a hundred farms, only to discover that each farmer had their own unique approach. Determined to carve out my own path, I synthesised the knowledge I had gathered into a personalised methodology."

Vasant adds, "In my first year, I familiarised myself with documentation requirements, buffer zones, GMO seed regulations, and other pertinent aspects." Currently, their operations span across three distinct farm locations. Production, mostly processed on-site, mainly focuses on fruit forest, including mango, lemon, guava, passion fruit, bananas, and tomatoes.

Participatory Guarantee Systems

Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) offer an alternative path for organic certification. This approach involves stakeholders such as suppliers, consumers, technicians and other interested members from the community in the verification process. PGS is particularly suitable for local markets and short supply chains. According to IFOAM - Organics International:

"Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) are locally focused quality assurance systems. They certify producers based on active participation of stakeholders and are built on a foundation of trust, social networks and knowledge exchange."

Unlike Third-Party Certification, PGS rely on peer-to-peer-inspection. Members of the PGS group visit each other's farms to assess compliance with the communally agreed-upon standards. These inspections foster trust and understanding within the community. Registered PGS initiatives are present on all continents, as illustrated in a global map by IFOAM - Organics International.

Registered PGS initiatives from IFOAM as of May 14 2024.

Blue markers are recognized by IFOAM

Green markers are recognized by local authorities

Yellow markers are self-declared PGS (under development or operational)

Fernando Melgarejo Prieto, a field technician at the Asociación de Productores Orgánicos (APRO) in Paraguay , describes the PGS process as (translated from Spanish originally) “... characterised by the shared and solidarity responsibility of members who are part of the system.”

Fernando, who has 20 years of experience working with organic certification and agroecology, says that PGS is important because it involves several sectors.

“It encourages the participation of various social actors related to food production, processing and consumption.”

He emphasises that PGS builds trust between producers and consumers, promoting transparency and reducing costs for farmers.

Fernando inspecting a fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) plantation at an organic farm in Paraguay.

Oliva Pérez González has been farming as part of the Tijtoca Nemiliztli PGS network for six years now. She lives in Casa Viridis, a farm located in the community of Tenango, municipality of Tetlatlahuca, state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. Oliva says (translated from Spanish):

“Participating in the certification processes gives us the opportunity to develop skills in economic, social, and cultural aspects. I feel happy and satisfied to care for the environment, where everything revolves around the balance between people and nature.”

Farmer Oliva selling diversified products from Casa Viridis farm, in Tetlatlahuca, Mexico.

Casa Viridis cultivates vegetables, nopales, fruit trees, aromatic plants, and vines for wine production, all on a quarter-hectare plot of land. Products are sold to restaurants, natural food stores and directly to families. Oliva adds:

“We have learned to value not only the economic aspects but also the establishment of community networks. I decided to certify myself to improve my processes while caring for my family and consumer families.”

LiteFarm’s Support in Organic Certification

Regardless of the chosen process, obtaining organic certification demands substantial effort by farmers. They are required to keep comprehensive records of their farming practices, materials used, and sales to prove adherence to organic standards. These requirements can be daunting for many farmers, but LiteFarm is designed to simplify this process.

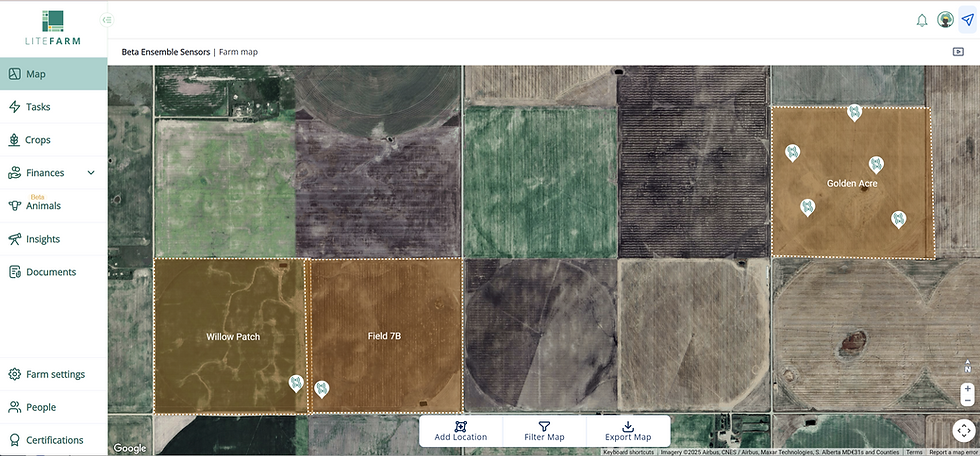

The platform supports organic certification efforts by allowing farmers to easily generate and export detailed reports. These reports cover the information most central to organic certification, including: crops, suppliers, and inputs. Additionally, LiteFarm enables farmers to share or download their farm map, which can be a valuable asset during the certification process. Learn more about LiteFarm’s certification export feature by reading one of our previous articles.

Some of the certifiers displayed in LiteFarm for Canada.

LiteFarm can enhance the certification process for certifiers needing additional information with a customised survey. This survey can be used by the certifier to collect additional details required by specific certifiers and which LiteFarm might not be able to capture.

Example of a survey that can be displayed to LiteFarm users.

After filling out this survey, users can effortlessly export it along with their standard documents directly from LiteFarm. This streamlined approach not only makes the certification process easier but also quicker for users.

Facilitating organic certification is one of the ways LiteFarm is proud to support sustainable farming. If you have any questions about the LiteFarm app certification functionalities or want to collaborate with the team, don’t hesitate to reach out. We're here to help!

As always, happy farming!

The LiteFarm team

LiteFarm’s commitment to simplifying organic certification is commendable. By enabling farmers to generate and export detailed reports on crops, suppliers, and inputs, as well as providing customizable surveys for certifiers, LiteFarm streamlines the certification process . Similarly, in software development, conducting regular evaluations using a software audit checklist ensures systems meet industry standards and function optimally. Both approaches underscore the importance of structured processes in achieving and maintaining quality and compliance.

Organic certification demands clear communication and detailed documentation. Tools featured in best ai text generator scan help streamline content creation and support farms in maintaining accurate, efficient records.

Supporting organic certification with tools like LiteFarm helps farmers adopt sustainable practices more effectively. Mārtiņš Lauva explores similar themes in his work on economic models for sports development, showing how structured support systems—whether in farming or athletics—can drive meaningful, long-term growth.

Organic farming practices offer great benefits to both the environment and the food we consume. It's important to know how to cook basmati rice properly to retain its flavor and texture while enjoying the health benefits of organic products.